MAPLE: Reflected Light from Exoplanets with a 50-cm Diameter Stratospheric Balloon Telescope

ABSTRACT

Detecting light reflected from exoplanets by direct imaging is the next major milestone in the search for, and characterization of, an Earth twin. Due to the high-risk and cost associated with satellites and limitations imposed by the atmosphere for ground-based instruments, we propose a bottom-up approach to reach that ultimate goal with an endeavor named MAPLE. MAPLE first project is a stratospheric balloon experiment called MAPLE-50. MAPLE-50 consists of a 50 cm diameter off-axis telescope working in the near-UV. The advantages of the near-UV are a small inner working angle and an improved contrast for blue planets. Along with the sophisticated tracking system to mitigate balloon pointing errors, MAPLE-50 will have a deformable mirror, a vortex coronograph, and a self-coherent camera as a focal plane wavefront-sensor which employs an Electron Multiplying CCD (EMCCD) as the science detector. The EMCCD will allow photon counting at kHz rates, thereby closely tracking telescope and instrument-bench-induced aberrations as they evolve with time. In addition, the EMCCD will acquire the science data with almost no read noise penalty. To mitigate risk and lower costs, MAPLE-50 will at first have a single optical channel with a minimum of moving parts. The goal is to reach a few times 109 contrast in 25 h worth of flying time, allowing direct detection of Jovians around the nearest stars. Once the 50 cm infrastructure has been validated, the telescope diameter will then be increased to a 1.5 m diameter (MAPLE-150) to reach 1010 contrast and have the capability to image another Earth.

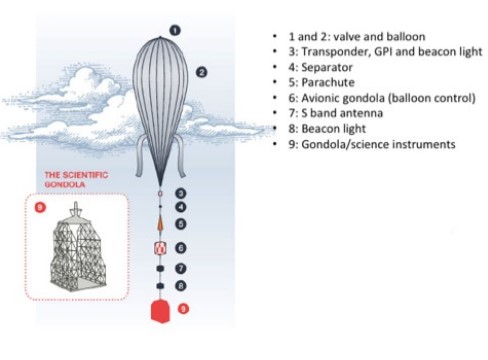

Figure 1. Typical stratospheric balloon components (from CSA website). |

1. INTRODUCTION

Over many centuries, science has made enormous leaps in understanding our place in the Universe; we live on a small rocky planet, orbiting the Sun in a large galaxy hosting hundred of billions of stars, just one among billions of known galaxies. The quest to find a second Earth in orbit around another nearby star, where life (as we know it) may exist, is one of the biggest challenges in modern astronomy.

During the last 20 years, the exoplanet research field has made steady progress toward taking the first image of another Earth. The first discovery of a gas-giant planet, similar to Jupiter, orbiting another sun-like star was made in 1995.1 The first images of gas giant planets orbiting other stars were acquired in 2008.2–5 Recently, the Kepler spacecraft and Doppler-based spectroscopic radial-velocity surveys have finally discovered Earthsized/mass exoplanets.6 We now know that they are numerous in our galaxy, from maybe one Earth-mass/size planet per system and with possibly 6% of Sun-like stars having an Earth twin.7 However, an important distinction needs to be made. While the Kepler and radial velocity discoveries are impressive, the technique offers limited data on the planets’ mass, radius and orbital configuration, but no information at all about the planet’s atmosphere and how Earth-like it is. Hence, the existence of a true Earth twin has not yet been confirmed.

Earth-like planets are defined as planets with a similar size, mass, and atmosphere as the Earth, and also located in the habitable zone of their star. The habitable zone being a temperate region around the star allowing liquid water, which could allow life familiar to us to develop. To confirm the planet’s habitability, a spectrum of the candidate planet’s atmosphere must be obtained to verify the presence of biomarkers (e.g. ozone, water, oxygen) and even signs of vegetation, land, oceans and seasons. Consequently, developing and applying a more direct exoplanet characterization method is the next step in answering this big question. Planets discovered with Kepler are generally too far away to allow direct characterization; Earth-like planet candidates must be found in the solar neighbourhood to allow this. Those few close-by terrestrial planet will be prime targets for in-depth characterization by a next generation of observatories.

Для продолжения чтения вы можете скачать полную версию материала по ссылке ниже